In the global pursuit of net-zero emissions by 2050, as outlined by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), hydropower is poised for a monumental resurgence. The ambitious scenario projects a need for over 2,900 gigawatts (GW) of total hydropower capacity, with pumped storage hydropower (PSH) contributing a crucial 420 GW for grid stability. While this hints at new projects, a significant, cost-effective, and swift contribution will come from a less visible source: the modernization, rehabilitation, and expansion of the world's existing hydropower fleet. Many of these plants, workhorses of the 20th century, are now 40, 50, or even 60 years old. Rather than letting them fade into obsolescence or embarking on capital-intensive and environmentally challenging new "greenfield" projects, the industry is increasingly focused on breathing new life into these assets. This comprehensive approach is not merely about repair; it's a strategic renaissance for sustainable energy.

Decoding the Terminology: More Than Just a Facelift The process of improving existing plants is nuanced and is categorized based on scope and objective:

- Rehabilitation: This is the core life-extension activity. It involves repairing or replacing deteriorated hydroelectric and electromechanical equipment to restore original performance and reliability. Think of it as a major overhaul to bring the plant back to its "as-new" condition.

- Repowering: This goes a step further by modifying the initial design to unlock more energy from the same water resource. This could involve installing a new, more efficient turbine runner, or even adding a new generating unit in a pre-designed but empty space ("unit addition").

- Modernization: This focuses on the plant's brain and nervous system. It involves integrating advanced digital control systems, automation, and modern SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems. The goal is to enhance operational efficiency, provide superior grid support services, and enable remote monitoring and control.

- Project Expansion: For plants with very long service lives (often up to 100 years), the original installed capacity may no longer maximize the site's economic potential. Expansion involves adding new generating units, which can require significant new civil works if not planned for originally.

- Project Redevelopment: When a plant's residual life is too short to justify rehabilitation, the entire facility—potentially including the dam and powerhouse—may be redeveloped with brand-new equipment, following fresh environmental and engineering studies.

The Compelling Case for Rehabilitation Over Greenfield Development

The shift towards rehabilitating existing infrastructure is driven by powerful comparative advantages:

- Economic Efficiency: Rehabilitation projects typically require 30-50% less investment than building a new plant of equivalent capacity. They bypass the massive upfront costs of new dam construction, extensive land acquisition, and new transmission corridors.

- Reduced Timeline and Risk: The development and implementation schedule is significantly shorter. Crucially, they carry lower hydrological, environmental, social, and permitting risks. The site is already developed, the water rights are established, and the community impact is understood.

- Performance Enhancement: Modernization doesn't just restore old performance; it can surpass it. Upgrades can yield 5-15% efficiency gains and increased output. This translates to more clean energy from the same water flow.

- Grid Stability and Flexibility: Modernized plants are better equipped to provide essential ancillary services like frequency regulation, voltage support, and rapid ramping. This makes them perfect partners for integrating variable renewables like wind and solar, balancing their intermittency.

Confronting the Enemies of Age: Common Degradation Issues Rehabilitation addresses a host of age-related failures that cripple performance and reliability:

- Turbine Deterioration: Cavitation—the formation and collapse of vapor bubbles—erodes metal surfaces on runners and wicket gates. Abrasion from sediment (like quartz) wears down components. Fatigue from cyclical loading can lead to runner blade cracking.

- Generator Aging: Stator winding insulation is a primary life-limiting factor, typically designed for 30+ years. Degradation leads to short circuits and failures. Rotor problems, including misalignment and poor concentricity, can reduce the critical airgap and cause catastrophic rotor-stator contact.

- Auxiliary System Decay: Step-up transformer insulation breaks down. Bearing performance degrades, and temperature monitoring becomes critical. Lubrication systems (oil and grease) develop leaks, leading to inadequate lubrication and damage.

- Changing Operational Duty: Many plants designed for steady "base load" operation are now cycled heavily to meet "peak loads" and provide grid services. This increases starts/stops from dozens to hundreds per year, accelerating thermal cycling in generators and mechanical fatigue in turbines.

The Critical Link: Operations & Maintenance (O&M)

Adequate O&M is the first line of defense. Data shows a stark contrast: for a 100 MW station, annual O&M costs can be $2.1 million (benchmark) versus $1.2 million (best practice)—a 45% reduction. Best practices include predictive maintenance (vibration, airgap monitoring), proper spare parts inventory, and trained personnel. In many regions, constrained O&M budgets lead to "run-to-failure" approaches, drastically reducing plant availability and triggering the need for major rehabilitation sooner.

The Hydropower Assessment Tool (HAT): Quantifying the Need Determining when and what to rehabilitate requires objective assessment. Tools like the Hydropower Assessment Tool (HAT) provide a structured framework:

- Reliability & Availability Screening: Calculates metrics like Reliability (8760 hrs - forced outage hrs) and Availability (Reliability - scheduled outage hrs). A drop below typical values (e.g., <98% availability for well-maintained plants) is a key trigger.

- Asset Trigger Age Screening: Flags components, like stator windings, that are approaching or have exceeded their expected service life.

The Rehabilitation Crossroad: Life Extension vs. Technological Upgrade

Once rehabilitation is justified, a fundamental choice must be made:

- Life Extension: The goal is to restore original specifications. Work includes generator stator rewind, turbine refurbishment (seals, gates), and bearing replacement. Output remains largely unchanged. The benefit is continued, reliable operation at known performance levels.

- Technological Upgrade: This seeks to capture the gains of modern technology. It includes everything in a life extension plus a new, high-efficiency turbine runner, potential generator core replacement, and modern ancillaries (e.g., digital governors, oil-free lubrication). The result is "Degradation Recovery" + "Technology Gain," leading to higher output, efficiency, and operational flexibility. While more expensive upfront, the Net Present Value (NPV) of an upgrade often surpasses that of a simple life extension due to greater revenue over time.

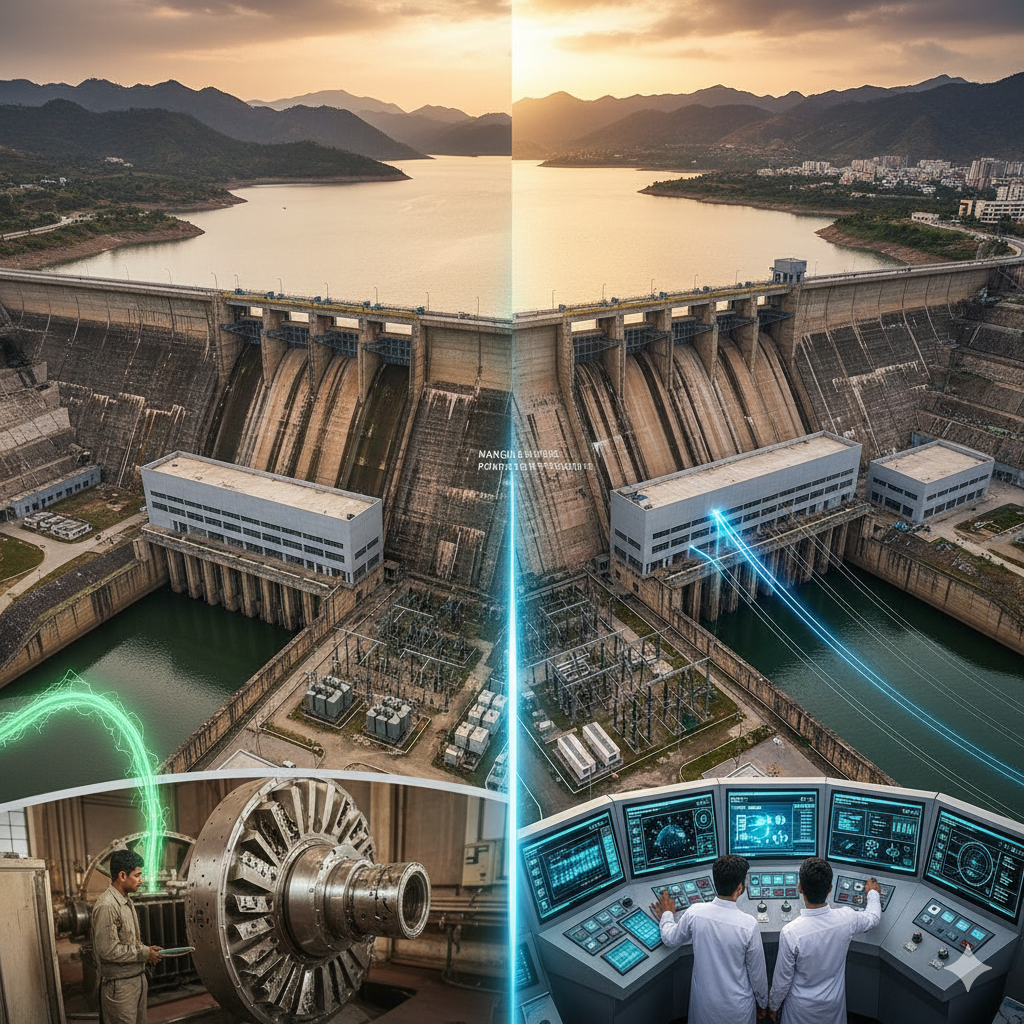

Example: The Mangla Power Station Refurbishment A prime example is the ongoing Mangla Refurbishment Project in Pakistan. Faced with aging units suffering from cavitation, sediment erosion, and obsolete control systems, the project embarked on a comprehensive rehabilitation. The scope is meticulous:

- Turbine Overhaul: Replacement of runners, refurbishment of wicket gates and seals.

- Generator Rehabilitation: Rewinding of stators, refurbishment of rotors and excitation systems.

- System Modernization: Installation of modern digital governors, SCADA systems, and protection relays.

This program aims not just to extend the plant's life by 30-40 years, but to improve its efficiency and ability to provide critical grid support, ensuring it remains a cornerstone of Pakistan's power system.

Conclusion: A Sustainable Strategy for a Net-Zero Future Hydropower rehabilitation is far more than a technical exercise; it is a strategic imperative for a sustainable energy transition. It represents a pragmatic, cost-effective, and environmentally conscious pathway to boost clean energy capacity, enhance grid resilience, and maximize the value of existing infrastructure. By investing in the intelligent renewal of our hydropower heritage, we are not just preserving the past—we are powering a cleaner, more reliable, and net-zero future.